Opinion : Wong Kim Ark at 125

In August 1895, a 24 year-old Wong Kim Ark set sail on the SS Coptic to go home and landed in the annals of history to forever change the course of Asian American history.

Wong Kim Ark had just finished visiting his parents in Ong Sing Village in Taishan, Guang Dong, and wanted to return to his birthplace in San Francisco.

The Collector of Customs, however, refused to let Wong Kim Ark disembark, because he asserted that the 1892 Geary Act, which renewed the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, excluded all Chinese laborers from entering the US, even if the person had birthright citizenship based on the text of the 14th Amendment.

In the federal District Court, Judge William Morrow disagreed with the Collector. A Chinese person specifically excluded by a congressional act still retained his birthright citizenship.

As immigration law expert Lucy Salyer from the University of New Hampshire pointed out, U.S. Attorney Henry Foote, influenced by legal scholar George Collins, had wanted to use the Wong Kim Ark case to erase birthright citizenship for all Chinese. Foote then appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) in U.S. v Wong Kim Ark.

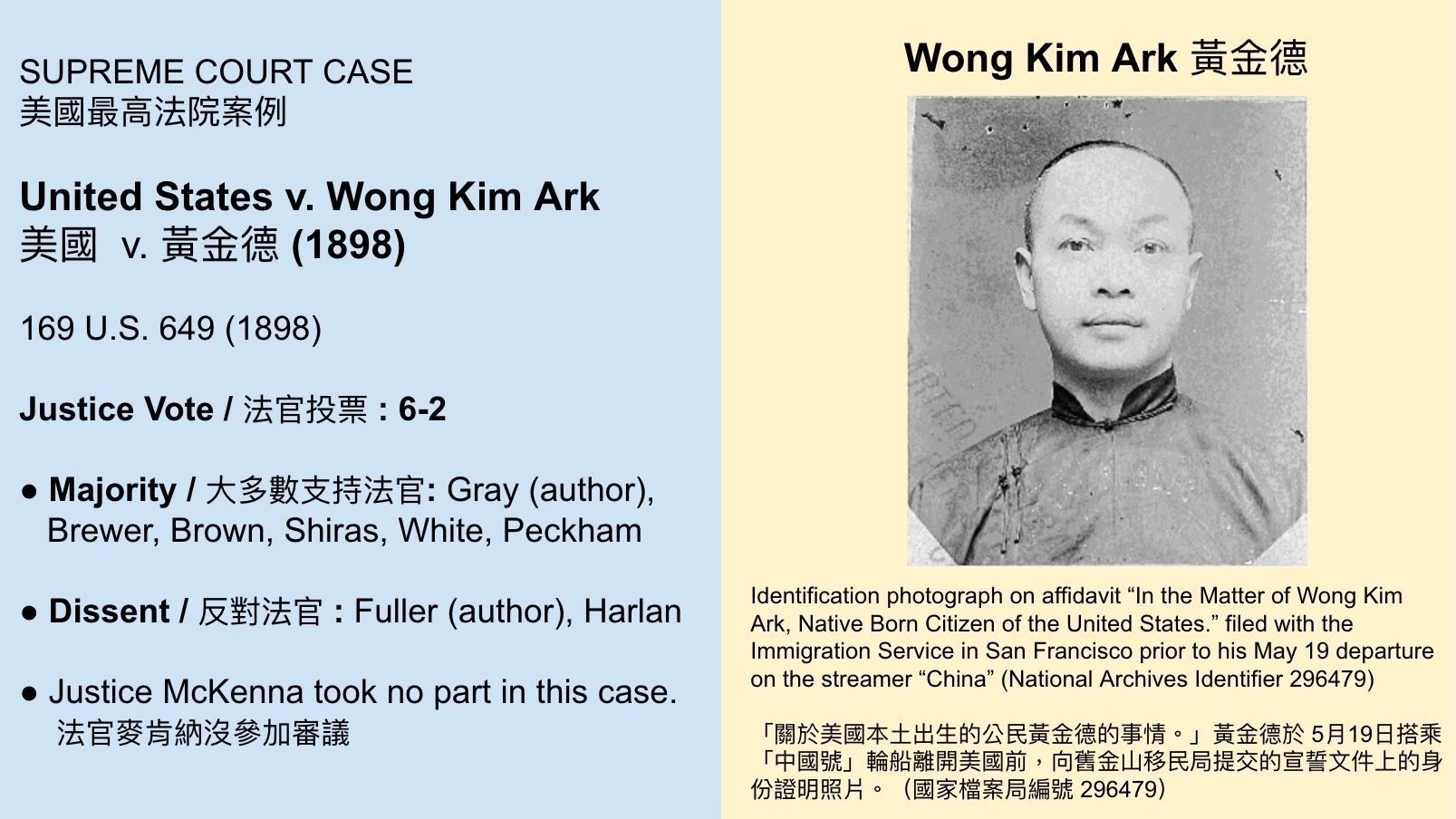

After a lengthy deliberation, SCOTUS on March 28, 1898, decided 6-2 in favor of Wong Kim Ark .

The decision meant that native-born Chinese had the rights and privileges of citizenship to immigrate, to travel, to vote, and to hold political office. It also meant that children born to a U.S. citizen anywhere in the world had the same entitlement.

According to University of Virginia Law Professor Amanda Frost, almost 50% (97,143) of all Chinese immigrants entering the U.S. between 1894-1940 claimed the rights of citizenship.

As historians like Erica Lee and others have pointed out: almost for certain, many made false claims by purchasing on paper their U.S. citizenship and became the eponymous “paper sons.”

In a contemptuous response to the influx of paper sons, the Bureau of Immigration created Angel Island in 1910 to scrutinize the claim of citizenship by demanding overwhelming documentation, enacting lengthy interrogations, instituting dehumanizing detentions, and engaging in invasive physical examination.

Indeed, Wong Kim Ark’s oldest son, Wong Yook Fun, got imprisoned for a month in Angel Island and failed to convince the immigration officer of his legitimate claim to U.S. citizenship. He was deported.

Nevertheless, these paper sons seeded the Chinese population in the U.S., until the 1965 Hart and Celler Act finally reformed the immigration policy to effectively remove the scourge of Chinese exclusion.

Without these paper sons, the San Francisco Chinese would not have reached a simulacrum of today’s vibrant community. Many generations of well-assimilated Chinese Americans would never have been born.

The Wong Kim Ark case also reveals an under-appreciated point in American history. Asian

Americans fought for civil rights and equality despite impossible odds and prevailing racial animus. Civil rights activism did not just simply begin in the 1950s as many often presume.

Legal scholars Charles McClain from UC Berkeley Law School , Gabriel Chin from UC Davis Law School, and others have well-documented decades of civil rights activism. The passive Asian American trope juxtaposes poorly with reality.

Moreover, the Wong Kim Ark case casts critical perspectives on the significance of 14th

Amendment in protecting all Americans and the congressional leadership in forging a more perfect union.

During the Senate debate over whether the 14th Amendment should extend only to Europeans and not to the Chinese, U.S. Senator Lyman Trumbull asserted: “The law makes no such distinction, and the child of an Asiatic is just as much a citizen as the child of a European.”

U.S. Senator John Conness from California who served in Congress from 1863-1869 courageously agreed to vote for the proposition that “children of all parentage whatever, born in California, should be regarded and treated as citizens of the United States, entitled to equal civil rights with other citizens of the United States.”

Even though 125 years have elapsed since the Wong Kim Ark decision, its impact still lingers. Certainly, the author and many readers of this article would not exist today to acknowledge and to appreciate Wong Kim Ark’s enduring legacy.

*Professor Thomas Jue is teaching at the University of California at Davis

- If someone’s vehicle blocks your driveway, San Francisco's 311 service will resolve it easier and safer for you

- U.S. Department of Homeland Security proposes green card status can be denied for Medicaid and SNAP recipients

- NAPCA Column 18: About the One Big Beautiful Bill Act

- San Francisco Real-Time Investigation Center (RTIC) equipped with drones and advanced technologies now fully operates to help keep the city safe

- The community blessed for two Chinese American Police Chiefs in a row to lead San Francisco Police Department

- San Francisco newly-appointed D4 Supervisor Alan Wong votes for Family Zoning Plan in his first full board meeting

- Opinion: My concerns about negative impact of road constructions to traffic and communities in SF’s Chinatown and Sunset

- Tech entrepreneur & political advisor Saikat Chakrabarti runs for Congress to fill Nancy Pelosi’s House seat