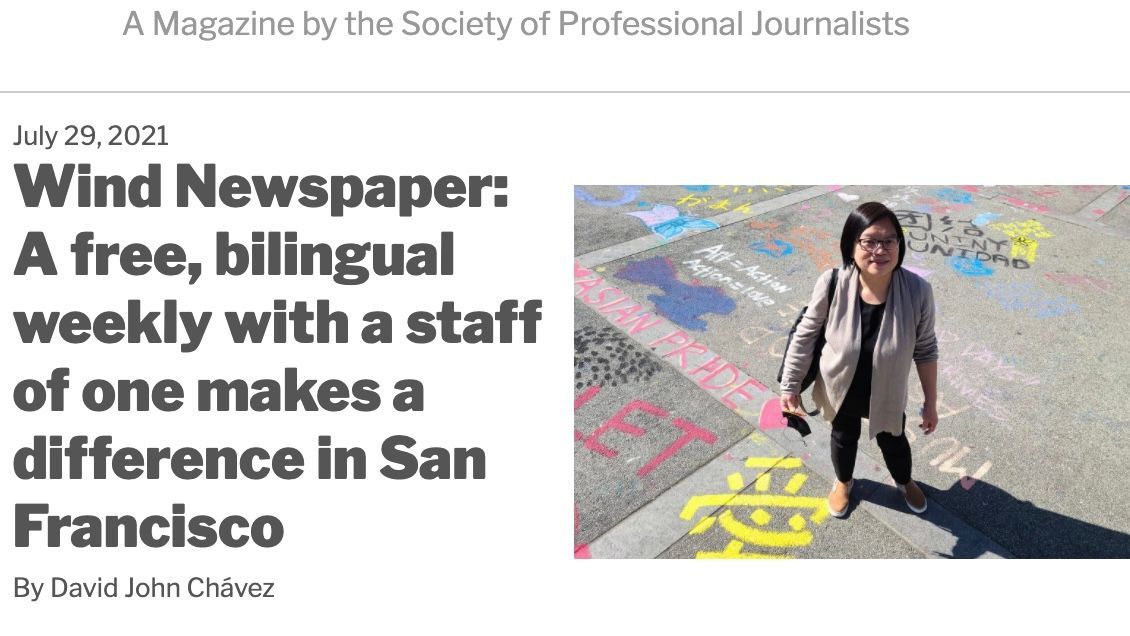

Wind Newspaper: A free, bilingual weekly with a staff of one makes a difference in San Francisco

*Editor's Note: Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ), a professional organization for all American journalists in the U.S. with 6000 members nationwide , publishes Quill Magazine quarterly. The summer issue of Quill i 2021 features Wind Newspaper and its founder Portia Li in the cover. We have received the permission from Quill Magazine to reprint the 4000-word article and translate the entire article into Chinese to share with our readers. Thank you SPJ and Quill Magazine for the support!

Every Tuesday and Wednesday, Portia Li makes the 45-minute trek north from her Millbrae home to San Francisco’s iconic Chinatown neighborhood. On a particularly gorgeous day, with a warmth that is the antithesis of the cool weather the City by the Bay is known for, she purposely parks on hilly Sacramento Street. On this day, she is hauling 3,000 copies of her publication, Wind Newspaper, which colorfully fills the trunk of her tiny electric car.

Grabbing one big stack of papers, she trudges toward the sky to drop them off at a market that houses one of her metal shelves. This market is one of 32 spots in and around San Francisco, mostly concentrated in Chinatown, where one can walk in and snag a free paper. After a quick chit chat with the cashier, she is off again, this time moving downhill, back to her car to grab another stack, ready for the next climb.

“This is good exercise for me,” she says gleefully, a hint of huff and puff in her breath as she moves to the next location.

After those few deliveries of the free weekly publication that gets snatched up quickly by the market’s customers, Li moves to another famous roadway, Waverly Place, and pops into iCafe Bakery, asking her friend and shop owner Hanna Zhang if she can sit down for lunch with food she’s going to buy elsewhere.

Once she gets a very enthusiastic green light, she goes to buy a lunch box of tofu, vegetables and rice at a tiny kitchenette run by another buddy. Next is a return to the cafe where she purchases a bottle of water to go with her lunch, which allows her to rest for a spell.

These dynamics play out multiple times for Li at many longtime Chinatown business staples. She is a reporter to the core, fiercely in love with this enclave, a historic relic adorned with Chinese lamps on streets such as Grant Avenue. Chinatown is a community that’s holding on despite the onslaught of big money businesses pushing their way in. Tech workers, who are here today and gone tomorrow, often jack up rent prices as a parting gift.

She is keenly aware that getting the story means talking to the right people. Breaking news and scooping the Bay Area’s media gatekeepers is something she’s been doing for years now. Li is old school and understands that building an honest relationship will get her the story. She is a grinder in a city that’s known for them.

By the time lunch is over, Li walks out of the cafe with a bag of mango mochi, a special pastry that Zhang doesn’t bake often but wants to make for Li. Sweet treats in one hand and a stack of papers in the other, off she goes to make another delivery.

Li has been working in the United States since 1984 after a three-year stretch as a general assignment reporter in Hong Kong. She went straight to Logan, Utah, and enrolled at Utah State University where she completed a master’s degree in journalism. Fresh-faced and eager to get going, Li jumped into Chinatown’s crime beat in 1986 for the World Journal, the largest Chinese language newspaper in the U.S. It was a no nonsense beat and the only gig available to the reporter who covered social welfare and transportation in Hong Kong. Street gangs, organized crime and illegal gambling were rampant in those years, and Li entered a white-hot fire, finding a satisfying challenge in the avoidance of getting burned.

She fell in love with the world of criminal justice, especially in the 1980s, where there was always a story to unearth. Her dogged pursuit of the roots of a narrative brought her major respect and credibility. She felt at home speaking with families of victims or criminals in English and Chinese, and was equally comfortable when dealing with power brokers such as district attorneys and judges.

One particular private investigator befriended Li years ago, a huge admirer of her work and one who saw firsthand what she did to keep the Chinese community informed. He had a prescient observation at the courthouse one day and shared it with Li, a simple suggestion that paid dividends later.

“He told me that people love to read my stories, and that I should start my own newspaper,” said Li. “I said there’s no way I can do that because it involves lots of money and lots of people. It’s not easy to start a newspaper.”

But at 10:30 p.m. on April 9, 2020, after 34 years of giving every ounce of her career to the World Journal, with countless bylines that broke so many stories on crime and politics, she was unceremoniously laid off through a phone call. The reporter with decades of experience, countless friends and sources, was now staring at an uncertain future, and had nothing.

Li’s sorrow at losing her career in an instant didn’t even make it through the night. Before Li’s head hit the pillow, she revisited the conversation she had years prior with that private investigator. The next day, Li was determined to get up and go to work on an entirely new publication: her own.

Staff: one.

Salary: none.

Costs: plenty.

From that April to September, with the global pandemic in full swing and cases in the thousands throughout the Bay Area, Li was planning for the initial launch of Wind (“If you want to know what’s happening in the Chinese community, follow the wind,” says Li, explaining the name of her paper, which makes her laugh hysterically).

All the while, readers would contact her, wondering where her byline went and inquiring if she was OK, which kept her motivated. Readers missed her and depended on her for news they couldn’t get elsewhere. Li, who became a household name in this world of longtime residents and family associations, disappeared, but she reassured those who reached out that she was about to make a huge comeback.

Li’s colleague Ben Kwon, who worked with her at the World Journal for 10 years, pulls no punches when he speaks of the decision by the publication to let her go.

“I felt so angry, because you have other reporters there who were not as qualified as Portia…why did they have to pick her? That was really stupid,” exclaimed Kwon, a retired freelance journalist who specializes in photography and travel.

Kwon saw up close what makes Li such a special talent.“This is my opinion, but most Chinese reporters don’t come from journalism school,” said Kwon. “A lot of them can read and write in Chinese, but don’t have the concept of how to stake out news, and can’t figure out what’s important and what’s not. Portia is different. After so many years, when something happens, cops call her.”

Wind is unique for a media venture in 2021. First of all, Li’s centerpiece of the publication is print copies for free. She wanted to prioritize the publication in both English and Chinese. She makes very little money on advertisements, prints every picture on the 20-page publication in more expensive color, and has used her life savings to continue working and providing critical information to the community.

At a time when online publications have decimated newspaper print, Li does things a classic way, pushing hard against the new models of journalism. In essence, at an age where she could retire and live comfortably, she has a different set of priorities in her early 60s.

“I’ve always been a person who has lived a very simple life. I don’t drive fancy cars and don’t really go to eat at restaurants,” says Li, explaining what allows for this venture. “I feel like if I can continue to contribute, I’ll just keep going and share with others instead of just being home. I’m a person that really enjoys working, not just for myself but for others.”

All through her day of distribution, she is stopped constantly and talks to everyone. There are the two young policemen who would love to chat but are off to handle a call, and a walk down famous Ross Alley means popping into a popular tourist stop, Golden Gate Fortune Cookie Factory. Kevin Chan, the gregarious second-generation owner of the nearly 60-year-old rustic shop with walls filled with photos of him and countless celebrities, digs deeply into a conversation with Li in Chinese. They are two local legends catching up with a passionate fervor.

“We haven’t seen each other in a long time,” says Chan, with Li nodding her head in vehement agreement.

Hanging out in her adopted community is a bit of a luxury these days. Getting to Chinatown to deliver her newspaper is one of many things Li has to do in a given week. When she’s not running around delivering the paper, she’s actively making the paper, which includes writing, interviewing, photographing and selling whatever ads she can. There’s a website to be updated, which her son helps with, and typeset to prepare for the printer. Here and there, she’s able to snag a volunteer who can write a story, such as Kwon, who loves sharing his many travel adventures.

Li has no formal roots in Chinatown, having never lived in the neighborhood, but she spent many years in San Francisco’s Sunset District before heading south to the suburbs. She makes no bones about one of her dreams — an office building on Waverly, which would give her unfettered access to the community she covers.

One of the reasons for the venture is her passion and commitment to people. Portsmouth Square, a large area where older Chinese residents gather for hours on end, is often populated with senior citizens playing cards beside the entrance to the vast parking garage it sits upon. On a typical weekend, the square is filled with residents and tourists, with beautiful sounds of the erhu penetrating the salty Pacific Ocean air hours before the misty fog rolls in and blankets the ancient buildings. Yet through the COVID-19 pandemic, gatherings at Portsmouth became more sparse.

The elder Chinese community rests heavily on Li’s mind. Because of her lifestyle and commitment, seniors have something fresh to read weekly in their native tongue, at no cost to them. Having the publication also in English helps to bridge the gap between native Chinese speakers and those who can’t read Chinese characters. Since September 2020, an elder could grab a brand new, freshly printed copy of a newspaper and have different stories while they sheltered in place.

Making a physical newspaper for the community at no cost to them doesn’t make great business sense, but for Kwon, it is quintessential Li.

“About six months before she was laid off, we had lunch and she told me, ‘When I retire, I want to try and open a bookstore.’ I told her that nowadays no one is reading books like that, but she is so determined.”

For Li, the calculation is very simple.

“If I was just staying at home, what would I do? But if I started my own newspaper, I can use my own savings that I’ve built for 30 years. Everyone laughed at me when I said that, but that’s true. That’s a fact. And I’ve saved some money.”

In the past year alone, Li’s voice has been amplified in all kinds of ways. A presidential election in 2020 that grew increasingly cruel and toxic by the minute made Li focus much of her pen on sharing reporting and perspectives to Chinese people.

“I know that elections mean power. Our community, because many are immigrants, doesn’t always know how big of an impact voting makes, so I always want to educate our community and remind them before elections to vote. That was one of my reasons I decided to start the paper.”

A reporter by default often wears the hat of a historian, chronicling critical moments in a community’s existence. Li is focusing much of her attention on trying to preserve Chinatown’s history, which is delicate and fragile. To that end, one of Li’s proudest moments is a story she wrote about Far East Cafe, the oldest restaurant in Chinatown. The establishment, in existence for the past 100 years, has incredible chandeliers and artwork on the first floor along with a massive banquet hall upstairs. It was slated for closure at the end of 2020, another cruel casualty of the pandemic. Once Li chronicled the story, more of the bigger outlets followed, and the restaurant was spared from the chopping block as attention was heaped onto such a staple of the Chinatown community, donations pouring in from all over. But Li posed a critical question to the community: If a place like Far East could close, what chance did other longtime Chinatown businesses have of survival? Ever the journalist, Li mortgaged all of her influence to help an institution in need.

Unfortunately, not every story is a bounce-back. In 2020, analyses released by the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University, San Bernardino reported a 7% decline of hate crimes in 16 of America’s largest cities, yet the crimes targeting Asian people had a climb of nearly 150%. Some horrific incidents in the spring of 2021 put the Asian community on edge, including the killing of eight people, six of Asian descent in multiple Atlanta spas and a particularly brazen assault on a 65-year-old Filipino woman in New York in broad daylight.

Li is actively covering this latest uptick, but for her, a lot of this isn’t new.

“It occurred 10 years ago against mostly older generations from age 50 and above, then it was stopped because of more police presence in the Asian neighborhoods in San Francisco for several years,” explains Li, adding that she has seen these violent episodes spike again since 2018.

What is different now, says Li, is the coverage.

“In the past, most of the news coverage on the violence was from the Chinese language media, but now Asian American journalists have joined us to cover the violence to keep everyone informed. It is how it becomes international news at the present time and also shows the impact and importance of work from all journalists.”

Despite the fact that Li has made her mark covering the more harrowing aspects of American urban life, it was her roots in social welfare reporting that informs what she does now.

“It’s even more difficult for the older generation, right? Physically, if they are not going out and meeting people, they are isolated. It’s not good for their mind, for their body, for everything. I started this paper because I just want to make them more active and informed with what’s going on in the community, the government, elections and the pandemic. That was really, truly the main reason I wanted to start this, and not charge any money for a copy.”

After 34 years of Chinatown’s citizens giving her tips, interviews, stories and treats, Li could have eased into a nice retirement and travel, something else she loves and deserves. Yet she has made it a mission to give her own gift to thousands in the form of 20 full-color pages of new information.

Getting some exercise every week on the hilly San Francisco streets is a nice added bonus.

*David John Chávez (he/him) is a Bay Area–based theatre critic and arts journalist. He has contributed to Theatre Bay Area, The Mercury News and American Theatre Magazine, as well as his own website, bayareaplays.com.

Twitter: @davidjchavez

- Do empty yellow loading zones best serve the San Francisco Chinatown community?

- T&T Supermarket, largest Asian grocery chain in Canada, announces to open at San Francisco City Center on Geary Blvd. in winter 2026

- (Breaking news: Charlene Wang wins in the Oakland's special election) Charlene Wang runs for Oakland District 2 Councilmember on April 15, 2025 to represent Oakland Chinatown

- Mayor Lurie announces plans to support small businesses including First Year Free program waiving fees for new businesses

- 12 speed safety camera systems out of 33 begin to operate in San Francisco by first issuing warnings instead of citations for 60 days

- Taipei Economic and Cultural Office extends services with opening of its permanent home in San Francisco

- Zu Shun Lei, 90, publishes his comic books to bring joy and laughter into the community

- Prop K opponents sue to stop permanently closing Upper Great Highway for an oceanfront park